Responses to Belonging in the American West

Collaborative Statement

Our research as a group parses out the complexities of Identity embedded in Place. The internal awareness of the struggle and vulnerability it takes to share our relationship to "the west" led to the creation of works exploring these boundaries. Not surprisingly, identity of place in the American West is complex. Our collective research as a group of visual artists has revealed issues ranging from the relationship with nature and survival, to personal identities and psychological dialogue of strategies to cope with our habitat. Life in the American West is characterized classically by rugged individualism, but it is more subtle than that.

While it seems nature can hold its own here in the west more than other parts of the world, how humans identify here is as complex and nuanced as anywhere. Seeing how artists documented and saw themselves in their environment, through this osmosis, we invented and tested new lenses to explore whether we fit into our own spheres. Situated in the dynamic interplay of environmental and psychological issues and relationships of the American West, including reconciliation with a murky past, our personal identities and psychological dialogues have emerged in diverse artistic inquiries. We established a new respect for the forgotten or nameless, whose voices and contributions intersect as threads on a woven blanket to become one.

Through research in library archives, museum collections, and in our own artmaking studios, we have examined how artists from the past portrayed and created their identities in reaction to their environment and contributed to a contemporary artistic and cultural inheritance. An internal awareness of the struggle and vulnerability it takes to share our relationship to the west has led to the creation of works exploring these boundaries. The works that have emerged from this examination ask viewers to reevaluate their own connections to eroding narratives embedded in Place, and identify with a sense of belonging.

Tess Wood

Introduction / Project Description:

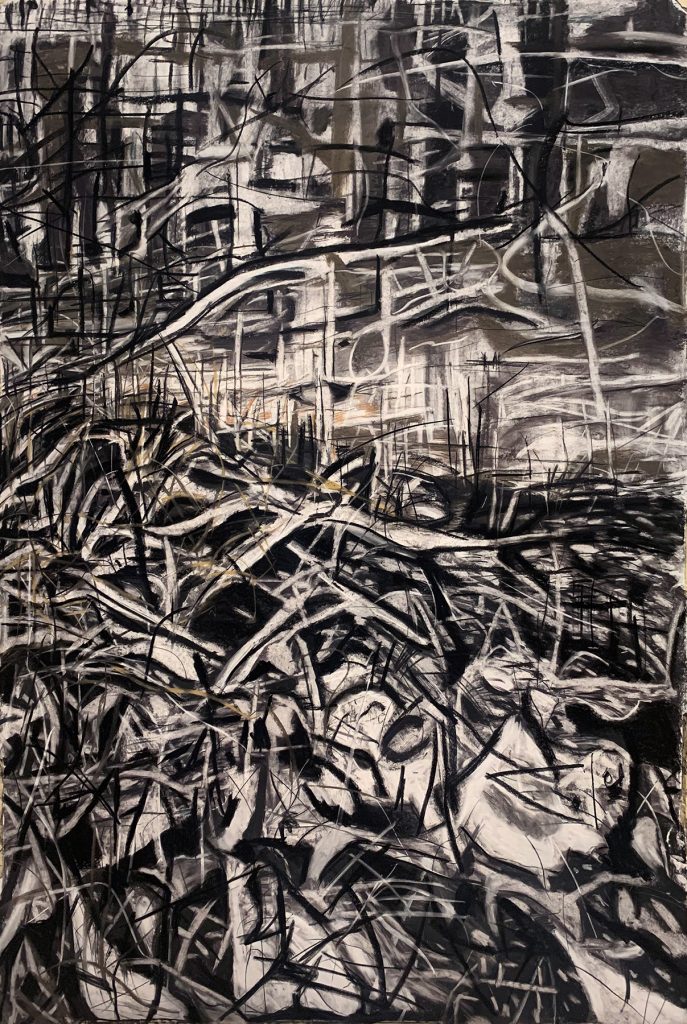

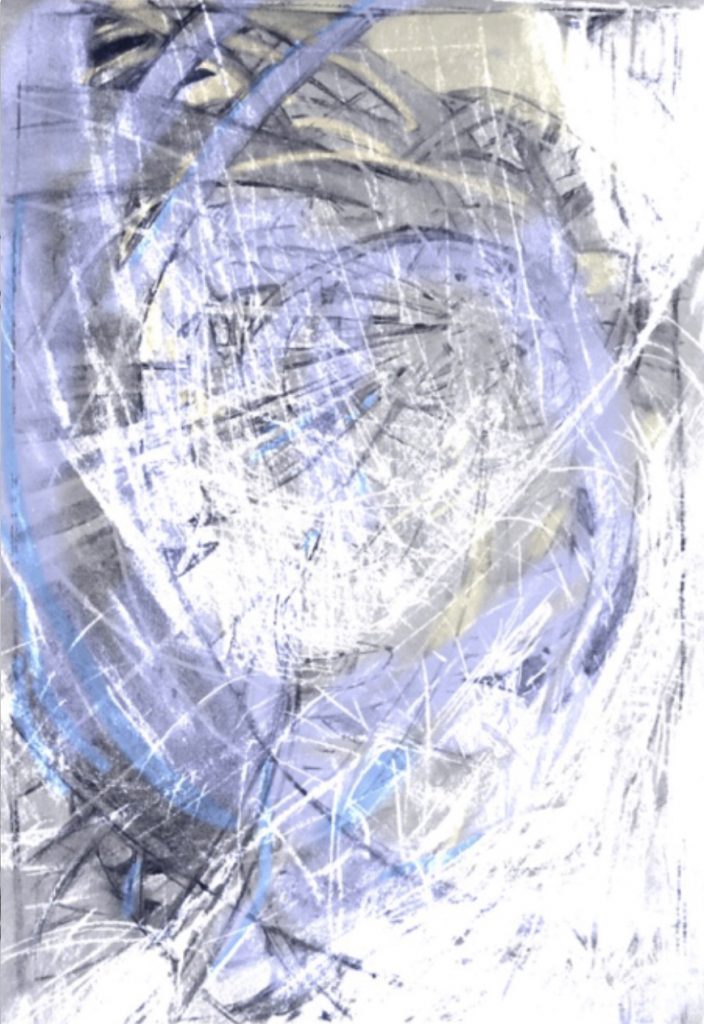

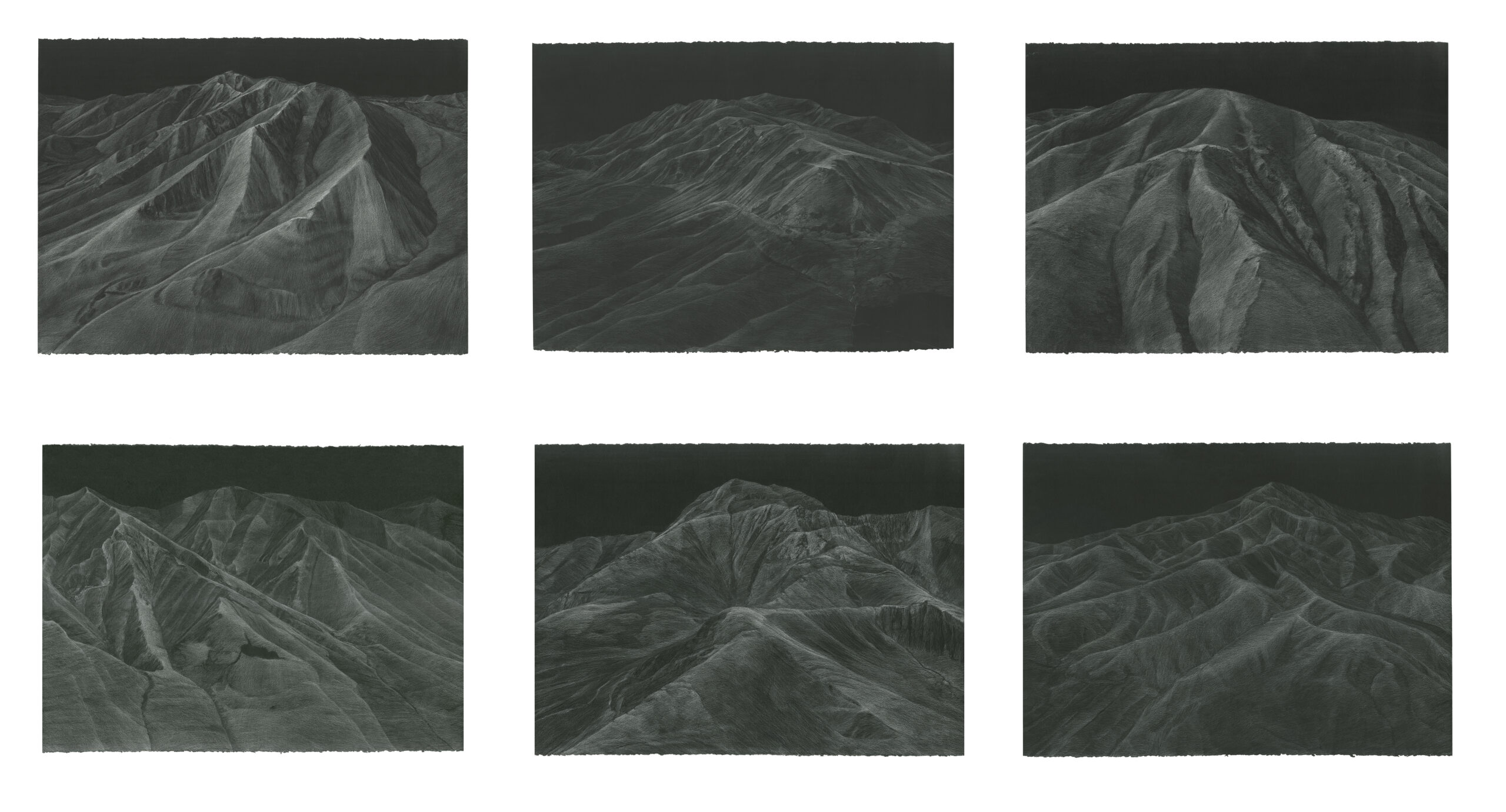

My project utilizes printmaking, drawing, and a combination of both media to explore how I fit into my surroundings, especially having not grown up in Utah, but the Pacific Northwest, a vastly different environment. Having family still located in Washington and currently fulfilling my residency in Utah, I exist in two places and have two locations that are my home. Through my prints and drawings, I am investigating through chaotic mark making what home means personally, and for me, that is the great outdoors.

Collection Item List:

UMFA1999.17.33, Michael A. Smith, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, gelatin silver print, 1975

UMFA2002.29.18, Michael A. Smith, Canyonland, Utah, gelatin silver print, 1993

UMFA2002.34.1, Michael A. Smith, Zion National Park, Utah, gelatin silver print, 1978

UMFA2002.38.1, Michael A. Smith, Blue Mesa, Arizona, gelatin silver print

Description of Work/How:

Using a collage system of various abstracted elements from personally taken photographs hiking throughout Utah, I have created four large-scale charcoal drawings of relatively similar dimensions. Each drawing incorporates tinted charcoal of an earth tone color palette. In a similar collaged fashion, I also created two large monoprints. After drying, I applied charcoal and color to enhance the print underlayer and vastly different marks obtained through this form of printmaking.

Dissemination:

My research has taught me a new approach to how I view my surroundings, reactionary instead of merely recreating an attractively compositional photo. Following my study of Michael A. Smith's abstracted landscape photography has led me to conclude how I utilize my photography as a reference in my drawings and monoprints. My works are self-expressionistic approaches to my childhood love of spending time in the outdoors. I am further interested in exploring connections between the chaotic mind and the tranquility obtained through being outside in nature.

While my works are more of a personal approach, their rich and chaotic nature allows my audience to form their interaction between landscape and the works' expressionistic form. I was recently introduced to the word pareidolia – according to Merriam-Webster, the tendency to perceive a specific, often meaningful image in a random or ambiguous visual pattern. I can see this being an intriguing avenue to explore down the road, especially when considering the chaotic mind through patterns and physical mark-making.

Since working on these specific drawings simultaneously to my large monoprints and viewing them side by side, I concluded that they lack an element that I obtain through my large drawings, whether through mark-making or building up materials and contrast. Since I am time constricted in having to print in one sitting, the 30 x 40 prints don't hold the same stimulant and experience. Therefore, I have begun applying my charcoal materials over the unique monoprint marks after the paper has dried for several days.

Eric Robertson

The central research question of this project explored the concept of belonging, and how visual artists have responded to a sense of belonging in the American West. Additionally, the project aims to question how a sense of place can be visualized using a diverse range of contemporary art language.

One aspect of the transition of the American West as it has witnessed a change from being populated with indigenous peoples to its current collection of European descendants has been how the natural world has changed as a response to how the land has been managed. For example, quickly after white men settled in the Salt Lake Valley, native grasses and willows were exterminated, leading to dramatic erosion along stream beds. Those native plants exist now in memories, drawings, photos, and some exclusive seed collections.

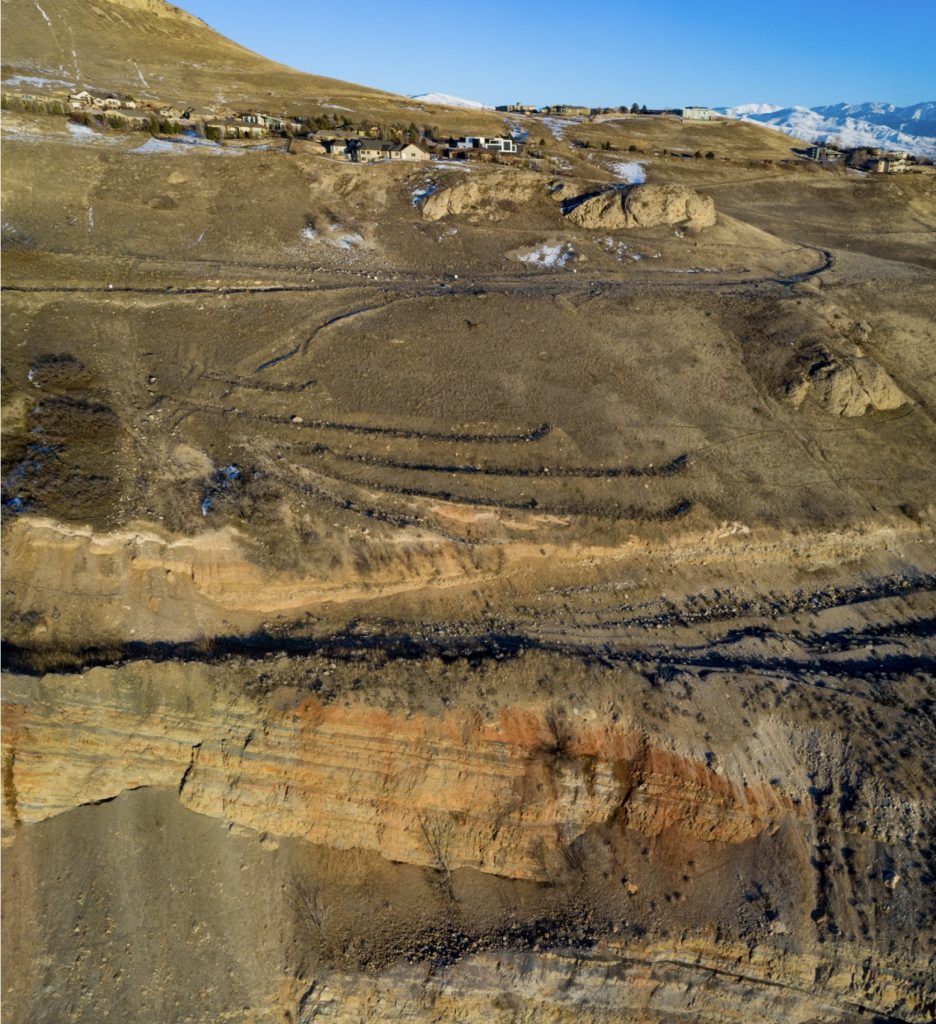

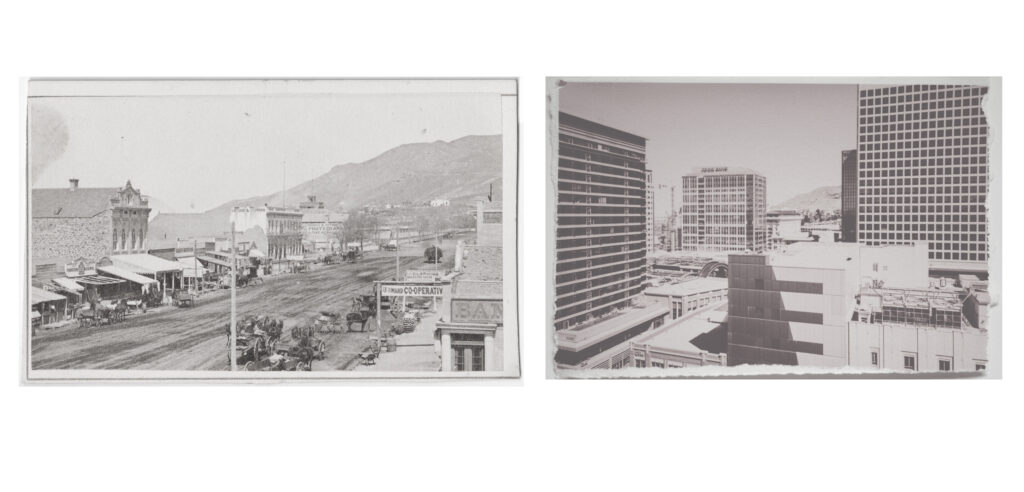

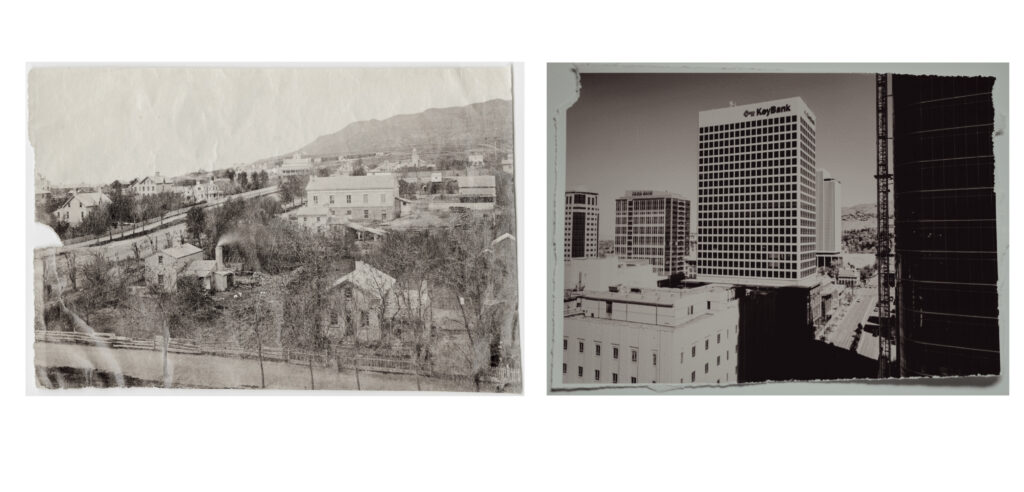

My specific research project focused on the evolution of the Wild-Urban Interface (WUI), that section of a developed community which interfaces with the boundaries of nature. I used imagery that depicted the WUI in the late 19th century and drone photography from today to provide a comparison of how this area has evolved over time.

Research Findings from Marriott Library Special Collection:

1. East Temple (Main) between First South and South Temple in Salt Lake City with the 13th Ward Co-operative and the Savage & Ottinger Buildings. Charles Roscoe Savage, circa 1865. Photo number: p0365n03_017front

2. Downtown Salt Lake City Street Scene. Charles Roscoe Savage. Circa 1865. Photo Number: p0365n03_01_002front

3. Northeast Corner of First South and State Street with the top of the Beehive House in the background (damage to unmounted albumen). Charles Roscoe Savage. Circa 1870. Photo Number: p0365n03_01_011front

New Work:

I made two new works as a result of this project. Both works focus on the view of the Northwest corner of Salt Lake City focusing around the area of Ensign peak. One work “City on a Hill” is a stitched panorama of houses living on the edge of the cliff at the northern end of the city. They sit awkwardly in space and feel somehow not at home in this challenging geographic terrain. This is contrasted by images from the 1860’s which show zero homes on said terrain. Another work, “Yesterday and Today, the SLC WUI” shows images from Charles Roscoe Savage alongside my drone photographs of the city. Viewers can recognize similar terrain but also are met with the extreme proliferation of trees throughout the city. This change in the flora and WUI constitutes a risk for increased wildfire damage and exploitation of natural resources, in particular, water.

Dissemination Statement:

The Wildlife Urban Interface (WUI) describes the location where settled towns and peoples abut non-developed land. WUI’s mark an important space where constant negotiation between humans and the natural world are actively occurring. The very fact that we have developed this term speaks to our innate sense of identity as not connected to nature. WUI’s happen everywhere, but many places in the East, Manhattan, for example, the WUI is basically obliterated. However, the American West has many examples of real confrontation within the WUI space. WUI policy making has impacts on wildlife, of course, but also wildfire prevalence and impact, water usage, and even home values and availability.

In Salt Lake City, the WUI has not moved very far thanks to our steep mountains that border us on one side and the lake front on the other. But, the way the WUI looks has changed quite a bit. In the 1870’s there were almost no trees and all the structures that people lived in were on the valley floor. In 2021, Salt Lake City now has millions of trees, and houses have been built perching on the edge of cliffs. The negotiation continues.

Christina Riccio

Introduction:

Revolving around themes of survival, my project considers a sense of place through the different methods humans have used throughout history to survive, both physically and psychologically. Beginning with the Utah pioneers in the mid 1800s, I reflected on the notion of pottery as a way to store and protect food- thus making it essential to survival. I also considered what survival means to me in the present day, how it goes beyond physicality and into emotional well-being. Mental health is crucial to my physical survival; and coping mechanisms are the vessels in which it is stored. Utilizing a combination of the utilitarian pottery of the pioneers, and playful illustrative representations of coping mechanisms, my project creates a sense of place through the juxtaposition of past and present methods of survival.

UMFA Collection:

I looked at a number of crocks and ceramic vessels in the UMFA’s collection for reference for my vessels. The following objects were influential in the creation of my own: UMFA2000.15.1 - UMFA2000.15.29_A,B. However, specifically my vessels were modeled after the following two objects: UMFA2000.15.5 and UMFA2000.15.29.

Marriott Library Collection:

Sheri Slaughter Utah Pottery Collection, 1858-2001

Folders 1-2: A History of Pioneer Ceramics and Potteries of Salt Lake City, 1850-1910

Folder 3: Old Wine in New Vessels: Transplanting European Art Traditions to 19th Century Zion

Folder 4: Pioneer Pottery of Utah and E. C. Henrichsen's Provo Pottery Company

Folders 9-10: Eardley Brothers Pottery Company

Description of Physical Objects:

I have created both two-dimensional imagery and three-dimensional pottery. The two dimensional imagery began as small ink illustrations on Bristol paper. These illustrations are simple representations of objects utilized in different coping mechanisms: medication, pill bottles, beer cans, etc. Alongside of these objects are additional illustrations representing emotions that come along with coping such as smiley faces, hearts, skulls, clouds, etc. These illustrations were then brought into Photoshop, digitized, and colorized. From there I created two patterns representing two coping mechanisms: binge drinking and medication.

The patterns are to be housed on two 40” vessels that I created in sections on the wheel. Each vessel was modeled after a specific crock in the UMFA’s collection. I have tested numerous methods for the transfer of these graphic images to the vessels such as: underglaze paper transfer, slip trailing, airbrushing, room temperature decals. I am currently finalizing my last tests utilizing slabs and bamboo brushes. Once the testing is complete, the illustrative patterns will cover the vessels like wall paper (as can be seen in the digitized examples below), and will be coated with a clear glaze.

Dissemination Statement:

In the mid-to-late 1850s, the Utah pioneers utilized wheel thrown vessels such as crocks, lidded jars, and churns to store and protect food for consumption. These vessels were key in many households to the safety of the nourishment they required for survival. Throughout the early days of the pioneers, creating the conditions necessary for physical survival (such as food, water, shelter, clothing, etc) was paramount to the continued existence of humanity.

However, in modern times, survival goes beyond physicality, and into psychological needs. Mental illness creates conditions in the mind that often makes surviving day-to-day life a struggle. As a neurodivergent human with both anxiety and depression, every day often feels like a fight between my logical self and the manifestation of my symptoms. Psychological survival requires more nuanced methods, and as a neurodivergent human, coping mechanisms are essential to my continued survival as a functioning member of society.

Combining the physical survival created through the pottery of the pioneers, with the psychological survival of my own personal coping mechanisms used to battle mental illness, these large vessels juxtapose the utilitarian nature of pioneer pottery, alongside of a more contemporary surface of cartoon-like drawings that represent different strategies for enduring my symptoms. The drawings on the surface are light-hearted in nature, both directly contrasting the serious nature of the topic, while also creating a playful sense of escapism I find necessary to survive. Through these vessels I am establishing a sense of place as a neurodivergent human in a neurotypical society.

Holly Nielsen

Description:

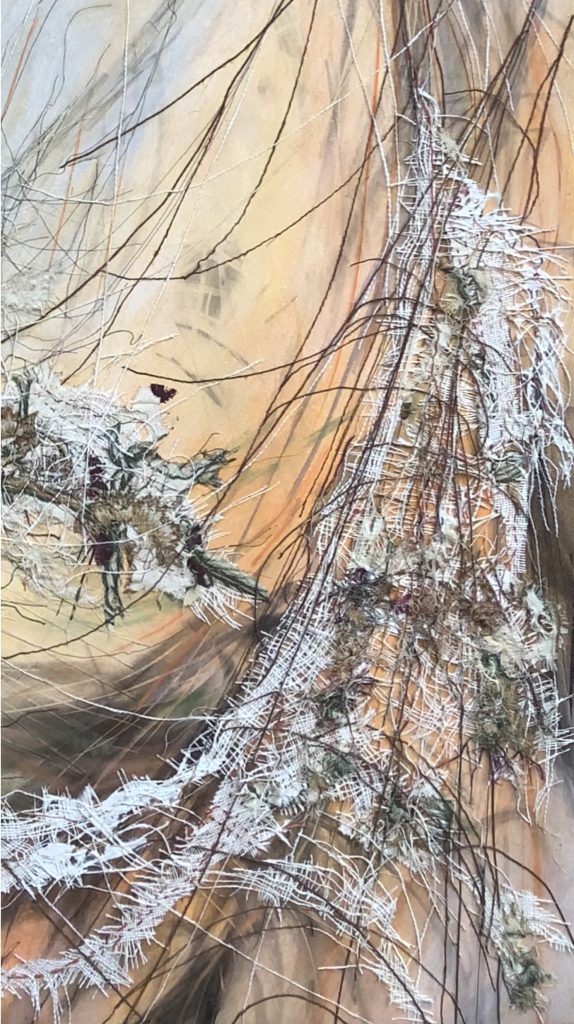

A 44"x 66" painting/collage on a gessoed Masonite board. Mediums; compressed charcoal sticks, acrylic paint, mat medium, cotton and polyester thread, burlap, and loose woven cotton fabric. In my process I created several layers of materials. First layers of acrylic paint washes and glazes, then layers of rubbed on charcoal via fabric and direct charcoal stick marks, erased out marks, and followed by several layers of thread and fabric applied with mat medium. Combining these materials, I formed shapes and lines into a motion of reaching, pulling, and weaving from background to foreground. This movement will represent the generational women who have been a part of the American West.

List of objects and items:

UMFA1978.245_B, UMFA1978.245_C, UMFA1978.245_A, UMFA1991.061.001, UMFA1995.017.001, UMFA2000.26.2.80, UMFA2000.26.2.79, UMFA1985.045.014, UMFA1985.052.353, UMFA2000.26.10, Anna Campbell Bliss, series 3, spectrum squared, variation C, 197, three screens print. UMFA 1975.046.007.002

Marriott Library Special Collections:

*Indian Wedding Ring quilt by Mary Hazel Norr Jorgensen 1063448 file name, 1878_03_04_AW65.pdf

*Bride's Bouquet quilts (Nosegay quilts) creature, Utah quilt guild. ID. 1065262, File name, 1878_11_07_H7.pdf, Double wedding ring quilt, by Polly Ann Deuel 1878_03_08_BC19.pdf, ID: 1062902 Spencer, Creator Utah Quilt Guild. Flower garden quilt by Henrietta Charolette Warnke

Wightman 1878_02_05_AW11.pdf. ID: 1064262. 1878_12_03_H38.pdf. ID: 1067696, Log Cabin quilt, by Sarah Elizabeth Crook Carlile. Maltese Cross Variation quilt, by Sorena Anna Peterson Malmgren. 1878_15_02_1L121.pdf. ID: 1072284 Silk Crazy Patch quilt by Nora Rae Crow Pechacek, 1878_13_01_K13.pdf.

Bosone, Reva Beck, Reva Beck Bosone papers, 1927-1977, MS 0127.

Johnson, Sonia, Sonia Johnson papers, 1958-1983 (inclusive) bulk 1978-1982, MS 0287.

Henry, Alberta, Alberta Henry papers, 1946-2005 (inclusive) ACCN 2069.

Esther Landa photograph collection, 1930s-1990s (inclusive) 94 items (92 black & white and color photographs of varying sizes, 2 35mm color slides) P0555.

Work description:

I first began my research looking through images from the UMFA archives, followed by research through the special collections from the Marriott Library at the University of Utah. One from the UMFA collections is of an Anna Campbell Bliss series 3 painting. Her painting spurred my mind with the concept of weaving together forms. I then looked up several objects such as blankets and baskets. These objects further my idea of forms coming together. Often women are associated with making baskets and blankets, making me wonder about the some of the women of the American West. I asked myself questions; who were they, what did they do, and why don’t I know about them? Through the library special collections, I research a handful of influential women who changed many communities in the state of Utah. These women were great movers and shakers and previously unknown to me. The dedication and action of these women woven into their communities forever benefited them. All these findings helped to influence several sketches and color studies, which were pieced together to form my final woven form.

Dissemination statement:

I’ve been drawn to visual patterns made by woven materials and stitches on fabric. I liken a single thread to a single person. If one combines threads/stitches they create a larger whole or form, like a woven blanket, mat, or basket. Individual women coming together to build their community or society create a larger whole or form. In my image some of the threads and charcoal and paint lines represent individual women. Some women who I’ve identified with through research and some unidentified women who have woven their communities. I’ve incorporated a single green thread to represents myself as I’ve become a part of these communities. I have chosen a color palette that mimics the colors of this landscape, which further ties these women to the American West.

In creating this visual coming together of shapes, colors, lines, and threads I have visually created a metaphorical coming together of women into a larger woven whole. In incorporating myself with these women of the past and present, who have come together to create a community, it has helps to define a sense of place for me in the American West.

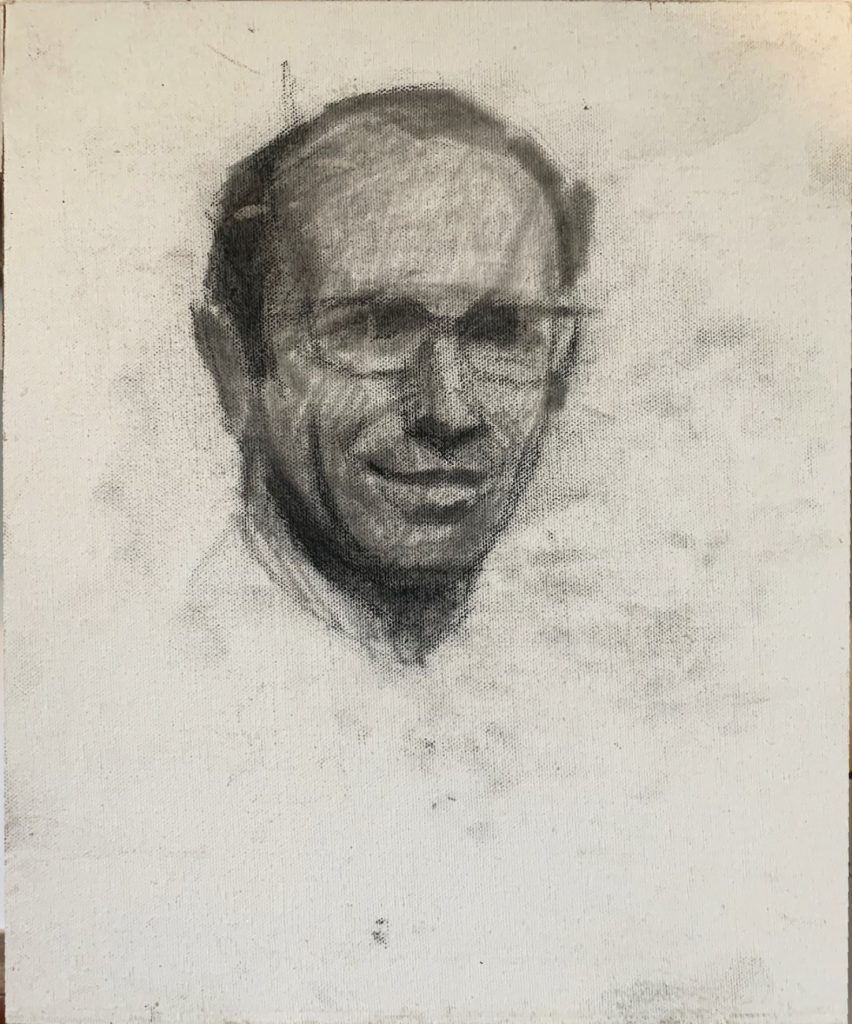

Bryce Billings

Following the central research question of how visual artists have responded to a sense of belonging in the American West, I have been researching the works of a prominent immigrant artist and their influence on painting, culture and education in Utah. Alvin Gittins was an educator and prolific portrait artist and had a profound impact on the arts community here in Utah. I was introduced to the paintings, mostly commissioned portraits of Gittins at a young age and was amazed at his ability to bring a tangible feeling of life to his subjects. My own artistic arch has brought me to a love of the figure and portrait, especially in the medium of oil painting. In my research I wanted to see the secrets of Gittins approach, career and collective works.

Following the central research question of how visual artists have responded to a sense of belonging in the American West, I have been researching the works of a prominent immigrant artist and their influence on painting, culture and education in Utah. Alvin Gittins was an educator and prolific portrait artist and had a profound impact on the arts community here in Utah. I was introduced to the paintings, mostly commissioned portraits of Gittins at a young age and was amazed at his ability to bring a tangible feeling of life to his subjects. My own artistic arch has brought me to a love of the figure and portrait, especially in the medium of oil painting. In my research I wanted to see the secrets of Gittins approach, career and collective works.

To start this research I contacted and interviewed Elizabeth Peterson, emeritus professor of Art History. Elizabeth spent ten years studying the work and life of Alvin Gittins, documenting, archiving and locating nearly 1000 of Gittins works. Through a 2.5 hour interview and subsequent emails, I learned of the life of Gittins, where he was trained and the influences and events that brought him to Utah. I learned how and why Gittins remained a little outside of the bounds of world recognition. Elizabeth shared much of Gittins approach, which was an insatiable need to keep at the easel and draw or paint, lining up sitters for 2 hour new pastel portraits, to two week commissioned portraits at a back to back schedule.

Elizabeth was kind enough to share her spreadsheet of locations of Gittins works, both on campus and throughout Utah. Off of this information I have tracked down and viewed over 20 of his works. Through observation and replication of various pieces, I have seen into the techniques, influences and changes in Alvin's development as an artist. There were many takeaways in this visual research. Gittins early works, late 1940’s and early 50’s lacked color, fine craftsmanship in drawing and a very Gittins distinct process of underpainting. I don't mention this as a critique of Gittins, but it was evident and actually gave me more encouragement that the better works will come with time and additional influences. Another insight came in the viewing of posthumous commissions. On a few occasions Gittins would take on a posthumous painting commission, working from photographs. These gave insight into the preferred process of observation from life, as these paintings lacked color specificity and depth. They were completely devoid of life color and even accurate light logic. This was a critical discovery, as it points to Gittins skill as an in-person observer of the form and that life comes from observation, relying on our own intuitive processes to feel if something we create evokes life.

I continued research of the commissioned portraits by contacting Laura Snow, special assistant to the president. Through interviews with her and locating the official archived documents on University commissions, I have been able to view and photograph all portraits that Alvin painted for the University. To view these in one sitting was both impressive and enlightening. Elizabeth Peterson had mentioned to me that Gittins loved to engage with a sitter, watching for clues to their personality via body language and other subtle cues. Laura had a unique insight to share, in that her own father had been the subject of one of Gittins paintings and shared with me how her father had a distinct way that he would sit, and that Gittins had emulated that perfectly. I have been studying the images of Gittins work held at the UMFA, and have noticed the similar pattern of early works lacking in color and distinct drawing accuracy. I have also seen in this collection some of the few narrative pieces Gittins created as he was primarily a portrait painter.

In addition to these areas of research I talked with Vern Swanson, a well known art historian and Emeritus Director of the Springville Museum of Art. He spoke with me about Gittins' career and about the narrative works Gittins created. Swanson had wanted more of these and in a way wished that Gittins would have given more to the art world in the form of meaningful and memorable works. I understood aspects of an art historian wanting talent to be recognized but also that of an artist wanting to pursue their love. In conversations with John Erickson, a previous student of Gittins, John stated that Alvin’s dream of heaven was an endless stream of models approaching the easel.

As part of my research I studied and observed images from the UMFA and the photo archive in special collections at the Marriott Library. In addition to these I made sketches and copies of two of Gittins works at various buildings on campus.

In the UMFA collection two pieces stood out that helped me gain a sense of Gittins techniques and intentions as an artist. The first being Le Mariage Demeuble, Object ID UMFA1970.007.001. This is one of Alvin’s very few narrative pieces. It depicts an older couple in muted tones with a story of an unsettled relationship. What is notable is that even in this not so beautiful story Gittins showed his love of dynamic composition with sweeping gestural arches carrying the viewer through the form. Also helpful in the collection was a rare still life circa 1963 Object ID UMFA2001.16.1.

In the Marriott’s collection I was able to gain insight into the personality and character of Gittins through looking at historical documents such as the “Portrait of a Portraitist”. This book published after Gittins' death shared his views on art and realism; It contained descriptions by friends and colleagues of his process and personality. Also in the Gittins papers were clippings and articles about his sitters such as Emperor Haile Selassie I of Egypt, and Dr. Edward Ichiro Hashimoto. These articles saved by Alvin showed that he was friends with and wanted to know more and look deeper into the lives of those he painted. I viewed many photos from the photo collection that gave me insight into Alvin’s thorough approach. I saw reference photos of sitters and then could compare them to finished paintings and see how Alvin always made them seem distinguished. I could see where supporting items such as a typewriter in the background required their own photos so he could paint them just right.

In the Marriott’s collection I was able to gain insight into the personality and character of Gittins through looking at historical documents such as the “Portrait of a Portraitist”. This book published after Gittins' death shared his views on art and realism; It contained descriptions by friends and colleagues of his process and personality. Also in the Gittins papers were clippings and articles about his sitters such as Emperor Haile Selassie I of Egypt, and Dr. Edward Ichiro Hashimoto. These articles saved by Alvin showed that he was friends with and wanted to know more and look deeper into the lives of those he painted. I viewed many photos from the photo collection that gave me insight into Alvin’s thorough approach. I saw reference photos of sitters and then could compare them to finished paintings and see how Alvin always made them seem distinguished. I could see where supporting items such as a typewriter in the background required their own photos so he could paint them just right.

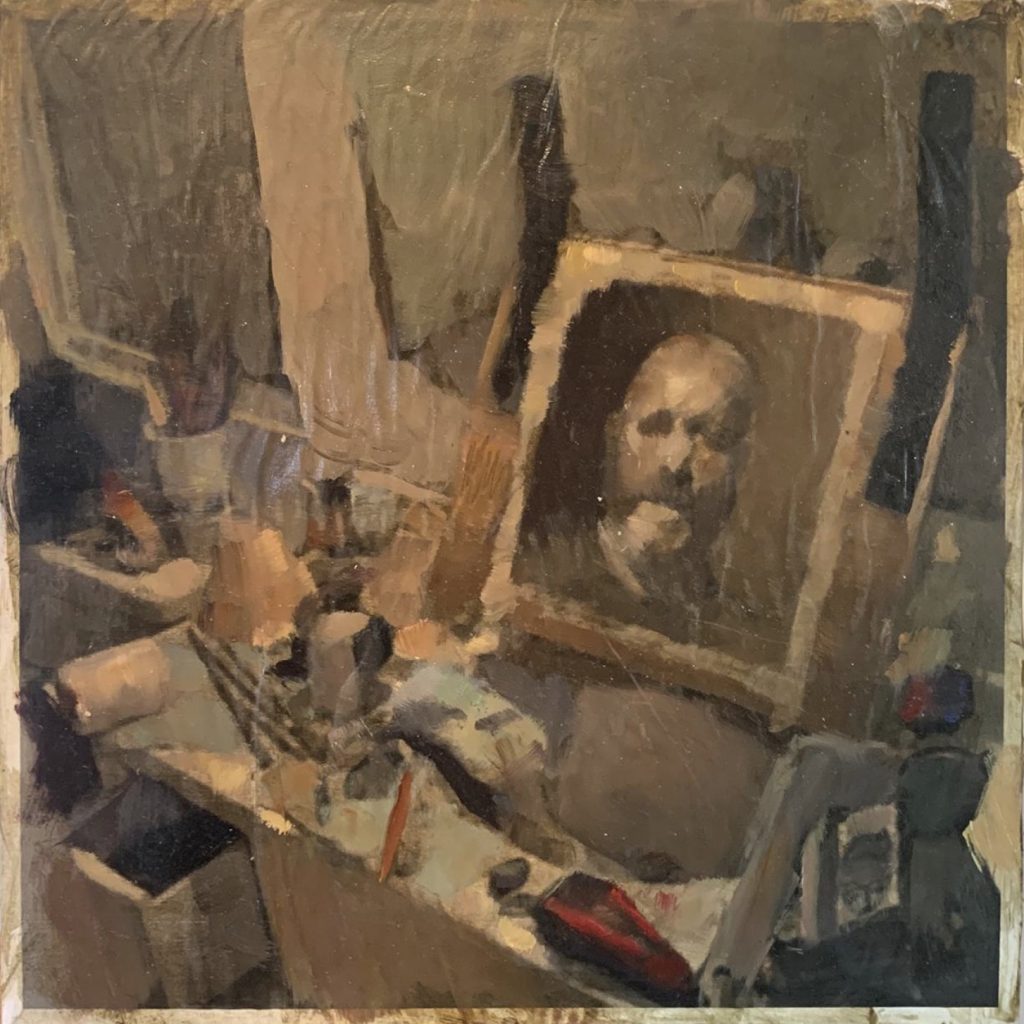

For my own personal research into Gittins technique I painted or sketched from his works. Being those of David Gardner in the Park building and one portrait in the business building. Later after these sketches I applied as an experiment Gittins palette and technique to an inanimate object to see if the life in skin color could be felt on a non-living object. Following Gittins approach of working from life I began a color sketch of my final piece as to have good color information when working in the studio.

In observing works, documents, and having interviews with artists, researchers and associates of Gittins, a portrait of the artist started to emerge. Gittins had a style and knack for seeing the idiosyncrasies of his subject, a subtle way that they held themselves. He worked mainly from life and the paintings were always better if he could observe directly. His work changed and evolved over time, with better observations and colors being placed with higher skill. In studying his life and work I found kinship to his upbringing life and events. Gittins served an LDS mission in England as I did, studied academically, and divorced in the midpoint of his life. In seeing who the man was I compared this with the works he created. I saw how Gittins presented himself to the world.

At the culmination of a graduate degree I am looking at how I will present myself to the world through my works. This semester as part of the Sense of Place research grant I created a work that explores this topic of the relationship of the artist to the viewer and how we compose our portrait to the outside world. The scene is that of the artists bathroom, placed before the mirror of how we see ourselves yet juxtaposed with the tools of how we compose ourselves to the outside world (toiletries, razors, hair clippers etc) as well of the tools of the painters craft (brushes, paints and charcoal).

With this piece and the research of an artist who defined his sense of place I wanted to explore my own. How will I craft my future, define and curate myself to the viewer and what is my relationship to them? How will I feel as though I belong? How will I gain a "Sense of Place"?

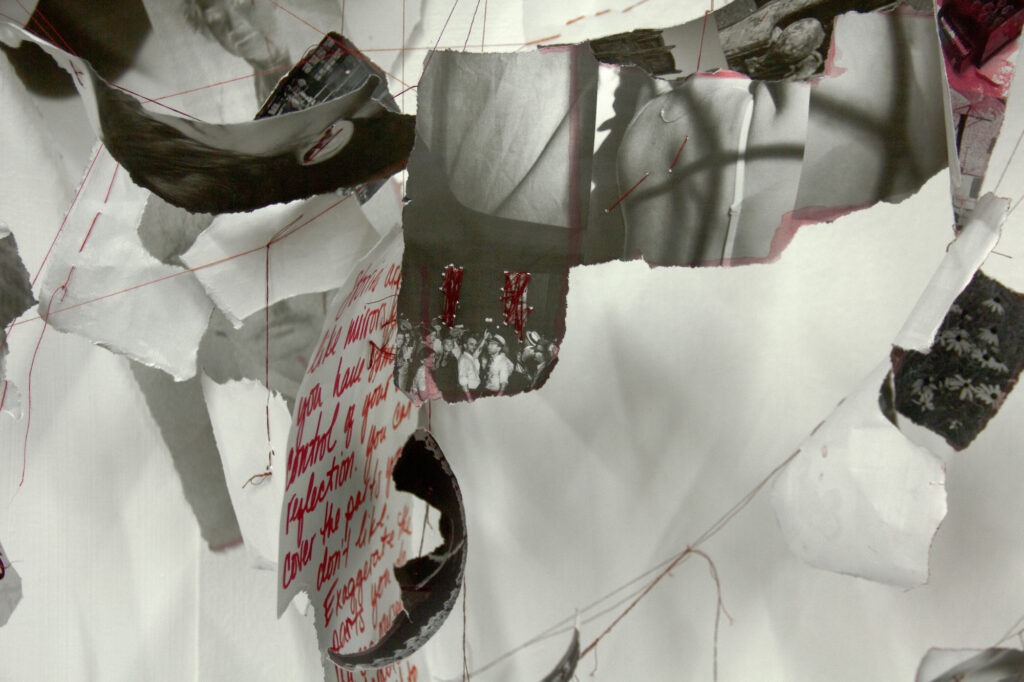

Candace von Hoffman

In the past couple of months, I have used Sense of Place as a prompt to continue my research focus on critical whiteness. At first, I kept that focus fairly broad as I find it very hard to find instances where academics ever even have to reference whiteness. As an attempt to explore solutions to this, I turned to the language, imagery and theory I have accumulated to critique whiteness from my personal experience growing up in Alabama. From a wall of notes I had in my studio, I turned to the online archives provided by UMFA and Marriott Library to search one word or phrase at a time and see what images came up. I began to see and critique the common themes white supremacist culture that runs like an undercurrent of American culture. Some imagery that I found very common in my reference to Alabama, I also found in reference to the American West. Utilizing a visual language that is informed by Western European traditions, my family photos, and public history provided by the University’s archives, I intend to initiate conversation about the mechanisms of white-centralized culture and what it is to exist in Western, White supremacist societies. I'm drawn to images that help my viewer find cracks in the façade of excellence that is constantly projected as “white standard.” I will assemble these images by piercing them, interrupting them and sewing them together in a tangled, visual network.

I am still working on consolidating my complete list of references for this installation, but as I continued to find relevant imagery, I had to come up with an answer of how to assemble this imagery and what material to use. As I have started to teach for the first time and during a global pandemic, I have been reminding my students of enjoying projects that have tactile processes- not to let everything on a screen where it can potentially contribute to Zoom burnout. I turned to myself with the same advice and decided to assemble an installation that expresses white fragility through the fragile state of rice paper. I decided to threaten and commit violence on the images I collected and printed by tearing into them and sewing them together in a tangled network of red thread. I also feel like adopting this process did a great job of helping me connect this project to my current sense of belonging in Utah. I am lucky to have the opportunity to work with other creatives and process their references as they share with me. The tangles in this installation become thicker and more complex as time moves and as a breeze passes through the work. Being an artist during this time has changed my practice and what it means to show up and share my work with the world.

We all attempt to adapt to the rapid changes of present times. We all try to learn, to accommodate, sometimes resisting, other times submitting to, whatever confronts us. Creatives go further than that. We take this ever-changing, shapeless confusion and transform it into an interpretation of our own devising. Creation in all forms is resistance. As my identity has become as fragmented, tangled and fragile as my installation, I ask myself: How do you make yourself legitimate, convince any community that you belong or contribute lasting, positive influence? Why? Who are you doing this for? The identity and history referenced in my installation has followed me my entire life, even before I was aware of it. As a child, I was told to feel proud and I did. I felt included in my family history while remaining ignorant to violent truths behind the land, money and history of oppression. Now, I am in a process of accepting the rage I feel towards this inheritance. The process of understanding my family’s relation to racism, violence and slavery has made my body anxious. Absorbing this history makes me anxious. I don’t want it, I can’t leave it behind. I think that this work is for me and my family first and for my community second. I have to process that I don’t belong in Alabama anymore and I never will again, but how can I contribute to my family legacy by processing this cracking facade of “Southern greatness”? I think I can attempt to atone for my family’s past through the honesty and education that this research requires. Is there space for compassion and for who? Yes. I am not religious but I believe that as human beings it is our responsibility to practice compassion and forgiveness. Without the hope for change there is no point in me continuing this work. As I take references to white supremacist culture from a personal space, to a local space, to a universal space – I attempt to demonstrate that this work is important for all white allies to embark on.

Reilly Jensen

Project Description:

My research examines the geographical and cultural margins of Central Utah and the influences they exert on the formation of personal identity on the landscape. Research on the landscape itself, and searching for remnants of history or memory within it, directed my research inwards towards excavating my own past memories born from the same Place. Specifically focusing on questions of Belongingness in Utah in my search I became aware of African-American Cavalrymen, Buffalo Soldiers, who contributed to federal establishment efforts to engineer infrastructure, establish and protect both White Settler and Indigenous Tribal interests from 1886-1918 on the Western Frontier of what is now the State of Utah. Not surprisingly, there are contradictions in the records of this history. These contradictions are integral to the formation of Utah and Utah identity, whether we are aware of them or not. My own sense of Belonging has inherited similar contradictions. Through research into the Buffalo Soldiers presence in Utah, I began to question whether Identity is porous and reacts to variables that construct Place. My sense of Belonging (or indeed, the formation of an Alien Identity) emerges from the contradictions and harmonies of Identity within a Place.

This has directly influenced the creation of my own artifacts and turning the focus on myself as a subject, to better understand how the rugged and rural environments of my childhood have shaped my sense of self, created agency, and pushed the limitations of who I understand myself to be. My work culminates as the creation of objects (as metaphors for my identity within Place) that exert and examine the contradictions embedded and tangled in our surrounding cultural and geographical landscape. Influenced and informed by my background in archaeology and my experiences living and working in the desert, I’ve highlighted commonalities between personal and collective cultural myths that become touchstones for personal identity. I am attracted to the layers of identity that solidify in rugged places that demand adaptation, self-reliance, and perseverance.

Description:

With storytelling as my goal, I used specific methods and materials (such as wet felting techniques to recreate sedimentary geological processes); and natural plant materials to convey identity and inheritance (noxious weeds and native plant species) to create new symbols of individual agency and empowerment. I constructed my Desert Witch Hat to express and reclaim aspects of my past that are subaltern (or "Other") to shape and create entry points to explore and dispel suppressed memories and identify noxious inheritance. With a particular fascination for material culture and use of symbol, I focus on teasing out the common threads between contemporary and past human experiences.

Personal Dissemination Statement:

In Sense of Place, I explore the ways knowledge of landscape, environment, and cultural memory intersect to create “belongingness” or convey “unbelonging” (i.e., alien status) within objects representing my identity. I am attracted to the layers that solidify in rugged places that demand adaptation, self-reliance, and perseverance. Using the tangling techniques of wet felting to mimic geographic processes, I let individual threads create their own sedimentary mat of connections that support cultural embellishments and convey the creation of social and personal myth. Incorporation of natural plant materials, using both native species and noxious weeds of Utah, speak to the contradictions between Belonging in a Place: Rabbitbrush is native to Utah but only “belongs” on overlooked, often disturbed liminal zones, while Myrtle Spurge, a noxious and invasive weed known to cause chemical burns and blindness, assimilates previously native habitat. These objects highlight parallels and contradictions about pluralities of identity to spark discourse about the agency of marginalized individuals, and the noxious inheritance of contemporary settler identity within the environment. Flipping between narratives and perspectives of marginalized histories, inspired both by archival materials (specifically early 20th century Buffalo Soldiers Utah history) and personal memory, the work is a negotiation and provocation that encourages beauty and complexity, endeavoring to break barriers between subject and object. I challenge the viewer to reevaluate their relationships to their own inherited narratives in Utah.

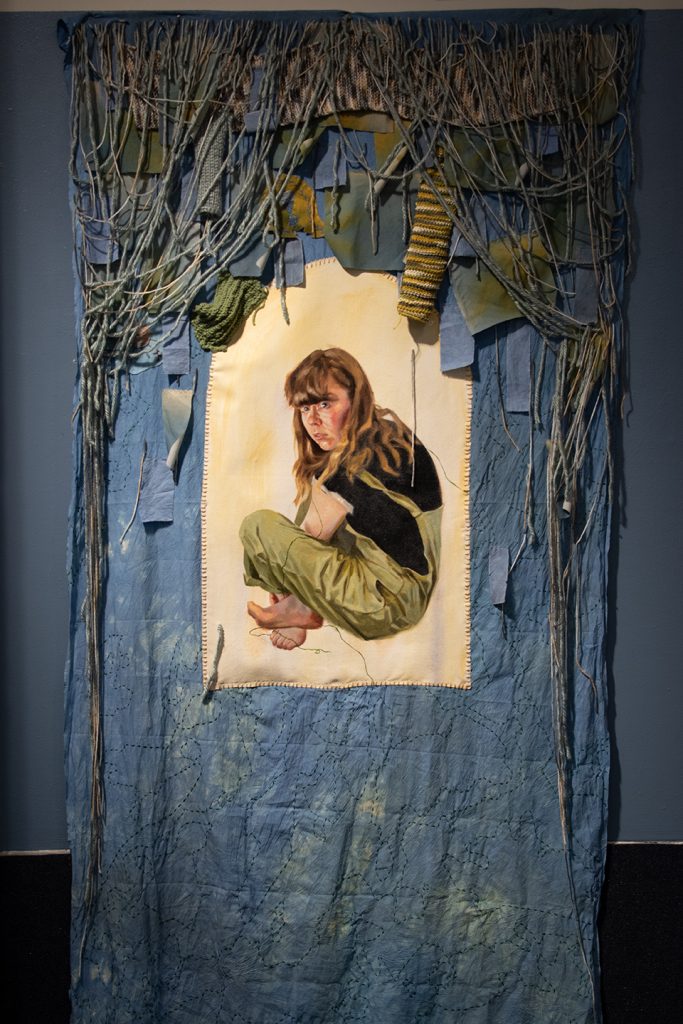

Hannah Nielsen

how my house got built, mixed media. 2021

Introduction:

This project builds on my existing thesis focus, which concerns the manifestation of internal conflict through the visual metaphor of art objects which combine Fine Art and Craft/Folk art elements. Consisting of three large fabric sections, or “walls”, how my house got built reflects on my relationship with Utah and its lasting psychological impact on my self-perception. This work plays upon ideas of interior and exterior through the use of “windows”, larger painted canvas pieces sewn into the walls, and topographical embroidery across the body of the textile piece. Essentially, the outside, Utah landscape, is placed on the inside, while the windows provide a glimpse at an illusionistic curated exterior image. Collaged textile and fiber elements hint at the presence of curtains, dripping thickly down the surface of the walls.

Research Items:

Anne Ryan, UMFA1977.205

H. Lee Deffebach, UMFA2002.42.1

Gary Hugh Brown, Ghost Riders In The Sky, UMFA1971.032.001

Angela Ellsworth, Seer Bonnets, 2008-Present. UMFA2010.16.1-3

Russell Talbert Gordon, A Good Place To Live, 1974. UMFA1974.070.043.022

Sas Colby, Gauze, 1979. UMFA1980.051

Description:

This project includes a set of mixed media/textile pieces composed of hand-dyed cotton fabric, embroidery thread, yarn and oil-painted canvas. There are three 4 ft x 8 ft pieces, and one 8 ft x 8 ft piece. These pieces use embroidery thread to imitate the topographical lines of Utah geographical areas surrounding a centered “window”, which is the painted component. It is intended to be a discussion of interior and external pressures in relationship to family/cultural heritage.

Dissemination Statement:

Green embroidery threads spill in carefully ascending loops across blue fabric, detailing the winding narrative topography of my life. These threads speak about my attachment to this land, a culture and environment which indelibly shaped my young existence. It is a story about love, and loss and conflict, indecision and compromise. Through this piece, I provide a window into that experience, while also placing it specifically within the Utah region. There is no aspect of myself or my personality which can be divorced from my Utah upbringing, or its strange and sordid chapter within the American West. Sense of Place allowed me to confront and engage with these stories, encouraging me to pull from materials and texts containing records of Utah history and art-making. Just as the elements of these tapestries fight against each other for aesthetic dominance, so too are my respective regional loyalties and grievances in constant warfare against each other. Ultimately, the formal and structural details of this series echo the messy complexities of a Utah heritage, and are all the stronger for their specificity.

Al Denyer

Research:

My research for this project focused on representations of Western landscapes in the UMFA collections. My initial focus was on the drawings in the collection by Albert Charles Tissandier. These works recorded not only Western landscape, but in some cases people and their homes. The traditional compositional elements used by Tissandier, function to increase a sense of depth and scale, yet the inclusion of figures and dwellings was fascinating as, I found that instead of an intended compositional tool or scale reference, their inclusion serves as a glimpse at the lives of First Nation and early pioneer settler groups of the West.

In further searching the UMFA collections, Tissandier lead me to the main focus of my research; Howard Stansbury, and his publication ‘An Expedition To The Valley Of The Great Salt Lake’ (Marriot Libraries Special Collections).

Howard Stansbury was tasked by the Corps of Topographic Engineers to lead an expedition to the Salt Lake Valley in 1849. The primary assignment was to survey the Great Salt Lake and explore the region around it, for the purpose of mapping a better wagon road as well as finding a potential route for the transcontinental railroad. Stansbury’s route ultimately became the one that the Transcontinental Railroad took when it was later constructed and finished in 1869.

Stansbury was the first surveyor to encircle and map the entire Great Salt Lake, using the relatively new system of triangulation, and the first to point out that the lake is a remnant of a much larger body of water. His report was re-published a number of times and was popular and informative reading for those considering re-locating to and making the journey West.

In Stansbury’s journal style of writing, his attention to detail along with his ability to accurately record his experiences is impressive. The expedition recorded species of birds, plants, lizards, and mammals, as well as rock samples and fossils. Many of the image references that I had discovered in the UMFA Collections, appear as illustrations in Stansbury’s journal.

I was naturally curious about the identity of the artist that created the drawings in Stansbury’s report, however no direct credit is provided, by the author. On further research, I believe that John Hudson could be one of the artists who worked on this project, and possibly Ned Kern contributed to images.

Stansbury’s sympathy and respect for the native populations that he encountered during his expedition, and the Mormon settlers of the Salt Lake Valley, was unique at the time, and still today elevates Stansbury as a respected contributor to the mapping of the Salt Lake Valley.

Dissemination:

‘A Sense of Place Chasing Stansbury’, is a series of drawings that I’ve created in direct response to sketches created during Howard Stansbury’s 1849 exploration and survey of the Salt Lake Valley. In searching for the geographic locations depicted in Stansbury’s work using Google Earth, I am intrigued by the alteration / beautification of landscape that occurs in recording or capturing geographic and geological features throughout history. My ‘re-depictions’ of these landscapes result in yet another level of removal from the actual place, questioning identity, memory and association.

UMFA list of items:

Albert Charles Tissandier, Marble Canyon Near Pagump Valley, drawing, 1885, UMFA1978.242

Albert Charles Tissandier, Marble Canyon, drawing, 1885, UMFA1978.234_A

Albert Charles Tissandier, Utes Under the Pines, drawing, 1885, UMFA1978.208

Albert Charles Tissandier, Desert Sunset, drawing, 1885, UMFA1978.200

Albert Charles Tissandier, House Rock and its Source, drawing, 1885, UMFA1978.217

East Side of Stansbury Island, Lithograph, 1853, UMFA1971.016.007.006

View of Part of the Western Slope of Promontory Range, Lithograph 1850-59, UMFA1994.036.003

Edward Laning, Untitled (Building the West), drawing, UMFA1994.005.001

Marriot Library list of artifacts:

Six mois aux États-Unis : the drawings of Albert Tissandier.

Tissandier, Albert, 1839-1906. Utah Museum of Fine Arts. 1986. NC139.T57 A4 1986

An Expedition to the Valley of the Great Salt Lake. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers. Stansbury, Howard. 1966. F826.U558 1966

John Hudson papers. 1826-1850. ACCN0674

Examples of work created:

About the Project:

In fall 2020 semester, Professor Al Denyer was awarded a Collections Engagement Grant to work on a group project with MFA students from her Graduate Critique class. These awards are part of “Landscape, Land Art and the American West,” a joint research and engagement initiative between the Utah Museum of Fine Arts and the Marriott Library supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and matching funds from the University. Denyer and her students conducted research using material from the UMFA and Marriott Library Special Collections, to explore what “A Sense of Place” means in historical and individual contexts, which will culminate in an exhibition of the work in 2022.